Early this morning, despite having promised myself I’d practice some social media distancing to avoid the overload of sad and scary news and views, I opened an article posted by a friend because the title caught my eye. “That Discomfort You’re Feeling is Grief,” by Scott Barinato, was posted on the Harvard Business Review site and at first glance, appeared to be organized into a friendly enough Q&A format. I tiptoed into the article much like entering a dark and creepy attic, with one eye closed and the other only partially open, as I was afraid of what I might find there.

Before I reached the first creaky board, I hastily exited the article, because right before my eyes was confirmation of what I already knew: it’s just too scary. After losing my husband Dan eighteen months ago and plunging into a level of grief I’d not known before, one that included isolation, fear, uncertainty, and sometimes hopelessness, I have only recently begun to see light again. I have been getting comfortable with a new outlook and new feelings. I have gradually become able to honor my past life while I enjoy the present. Sometimes, I even dare to look ahead to the future.

The arrival of a global pandemic (seriously, did we ever think we’d use these words??) has brought all of that to a halt, as I—and we—experience a loss not at all unlike the loss of a loved one. We are experiencing grief and all its visible and invisible grips on our senses and sensibilities. We are afraid and anxious and uncertain and untrusting and angry and sad as we slowly lose the lives we have lived and begin to glimpse the life we will need to live. And it does indeed feel all too familiar.

Anyone, which basically means everyone, who has experienced grief knows perhaps the most paralyzing feature is fear and that the fear most often comes from the uncertainty. We are uncertain from the beginning this loss even occurred and we may spend hours, days, months or even years trying to convince ourselves that even if it did, we might have done something differently to change the outcome. Even after we’ve accepted the loss to be certain, we face the additional personal and profound uncertainties of a life without our person, which touch every speck of our existence. We are uncertain about every moment and decision making up our days, from the time we arise to the time we attempt to sleep. And when the uncertainty is too much to bear, we just get sad. And then mad. And then maybe hopeless.

We can use a lot of time and energy right now to question how the loss of our previous lives began. Was it a guy eating a bat in China? Was it because we didn’t act quickly and prudently? We can also use resources and time to express anger when we think we know the answers. We can lash out at leaders and we can rant to others about spring breakers and underground gatherers. We can withdraw completely and hoard our food and necessities and hope for the best when we emerge. We can, understandably, become so worried and sad that we lose sight of a bigger picture and we can begin to indulge in a version of self-care that is actually destructive. We can overeat and drink alcohol to excess and use other mood-enhancers to temporarily numb our feelings, the whole time knowing when we wake up tomorrow we will face the same circumstances, only multiplied.

When this is all said and done (ish), how will we recall our responses and reactions and decisions? Will we be relieved it’s over and move on quickly? Will we be embarrassed or alienated because of any words or behavior that didn’t show us at our best? Will we be newly energized and motivated to live a new life that includes skills learned during our distancing period? What will we remember most? How will we honor the life we led before the pandemic while grieving the life we lost? If hindsight is truly 20/20, then 2020 is the year to put those lenses on. We can each take a look at lessons learned from previous losses as tools for dealing with our current loss.

I entered widowhood the same way I entered this crisis—unprepared and unwilling. I felt panicky and helpless and alienated by my former smart and resourceful self. Now, though, when I look back, I can use lessons learned during that period to more clearly see the present and also the future with restored confidence and awareness. I can recognize past emotions that will not serve me well and those that will. Grief teaches us many things, but the most valuable lessons are those we learn about ourselves. If we allow it, grief shows us we are strong when we need to be strong and it shows us when we need to rest and regroup. It is equally important to master both of these.

Looking back, I can see that even while grieving, when I needed to, I learned new skills. I learned to manage on my own all the things I used to share with my husband—household minutia, bills, auto repairs, decisions. Knowing I can learn during grief means I can continue to learn new things now. Why, just this morning, I participated in my first videoconference and I didn’t do anything to embarrass myself or disrupt the meeting!

Looking back, I realize while grieving I missed out on moments and events and opportunities that took place during a time when my sadness and fear kept me homebound. Now, I am required by the state to be homebound, but I know from looking back that I am okay at home. I know how to constructively pass my time and when to allow for periods of acknowledging how I feel. I know how to determine what is worth getting back and what is worth letting go of. I learned from looking back there is indeed for everything a season and a time and a purpose.

Looking back, I know my biggest hurdles during grieving were faced and conquered when I was taking the best care of myself. I now accept and own the responsibility for my very being, physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. To that end, grief has taught me to eat, sleep, move, appreciate, create, learn, and most of all, to love and to keep loving.

Looking back, I know, without a doubt, I would not have come through the period of uncertainty without the certain and undying love from friends and family. So now, because I’m quite able, I try and give back over and over. I stay connected regularly with family and friends. I serve others when and however I can with new rules. When this is behind us and we look back, we will certainly know that how we connected with and cared for each other was and will always be vital to our survival.

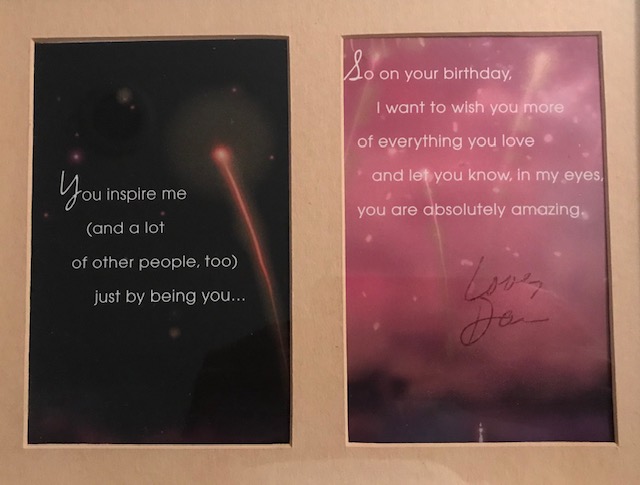

Looking back, I see maybe the most important new lesson I learned from grief was that I could experience both deep sadness and joy at the very same time and that was quite okay. Although I miss my husband in all the spaces of my heart, those same spaces hold fierce love for our daughters and their husbands and their babies and my family and my friends and my life. I have been overcome with sadness on birthdays and anniversaries and regular old nothing days without Dan. I have also laughed at our memories and enjoyed trips and events without him and celebrated with great happiness as our new grandchild arrived. I have realized by looking back that sadness and joy can coexist in a loving heart and this realization has allowed me to welcome new love and happiness, while again facing uncertain times.

Now, when uncertainty threatens to escalate to fear and I’m feeling its familiar presence, I can see from where I’ve been that grief only comes from experiencing great love. It is right for us to grieve now, as we face loss of life, loss of love, loss of freedoms, and loss of certainty. But we have seen and may we continue to see that these losses will reveal happiness and joy to us if we let them. If we can look back, we can look forward. Hindsight is 2020.